Funny Pictures of Appalachian Shacks Called Home

Ruby Cornett, 'I asked my sister to take a picture of me on Easter morning,' from 'Portraits and Dreams' by Wendy Ewald. Courtesy the artist and MACK.

In 1976, twenty-five-year-old Wendy Ewald rented a small house on Ingram Creek in a remote landscape in eastern Kentucky, hoping to make a photographic document of "the soul and rhythm of the place." As she writes in an essay included in the expanded new edition of Portraits and Dreams: Photographs and Stories By Children of The Appalachians, originally published in 1985, her camera landed on the "commonplaces" of Letcher County. Set in the Cumberland Mountains at the edge of Kentucky and Virginia, Lechter Country is in the rural, rolling, rugged, coal-mining heart of the still sprawling and still vastly misunderstood and frequently mispronounced region known as Appalachia (the correct pronunciation is Appa-LATCH-uh). More than a decade before Ewald's arrival, the publication of Night Comes to the Cumberlands: A Biography of a Depressed Area, by local lawyer and environmental crusader Harry Caudill, had helped spur John F. Kennedy and later Lyndon B. Johnson to declare war on poverty in Letcher County and regions like it. But Ewald did not intend to photograph "poverty," or to photograph the place in the reductive way it had come to be depicted. She was interested in the way the people pictured themselves.

She went to speak with a local school principal and, during the years 1976 to 1982, taught photography in three elementary schools, including a surviving one-room school called Kingdom Come, which was heated by a coal stove that the students took turns refilling. She sold Instamatic cameras to her students, "So they would value them as things they had worked for" as she put it, for the price of ten dollars, or its equivalent counted out in odd jobs. In the classroom she guided them toward a way of seeing born out of feeling and imagination, inviting them to photograph around themes of family, animals, self, and dreams. The resulting pictures, made in a mentored creative collaboration and collected in Portraits and Dreams, call up a music of the place only Ewald's students could hear and access; and thus the book amounts to a reliquary of a magic hour in the children's own lives, fleeting and resonant.

Ewald's students in those years were between the ages of six and fourteen. Some had to cross swinging bridges to reach the school bus. They were prone to disappearing into the creeks and hollers for long hours, adept observers of their own environments, and they were particularly attuned to seeing and speaking in a natural, unselfconscious poetry. "The mountains, I feel they have secrets like nobody has ever heard of," says a boy named Allen Shepherd in one of the book's accompanying texts, taken from interviews Ewald made with her students. "Hear the squirrels a cutting and a hollering." Robert Dean Smith: "Spring time makes you just want to slob up in the sun on the side of a hill."

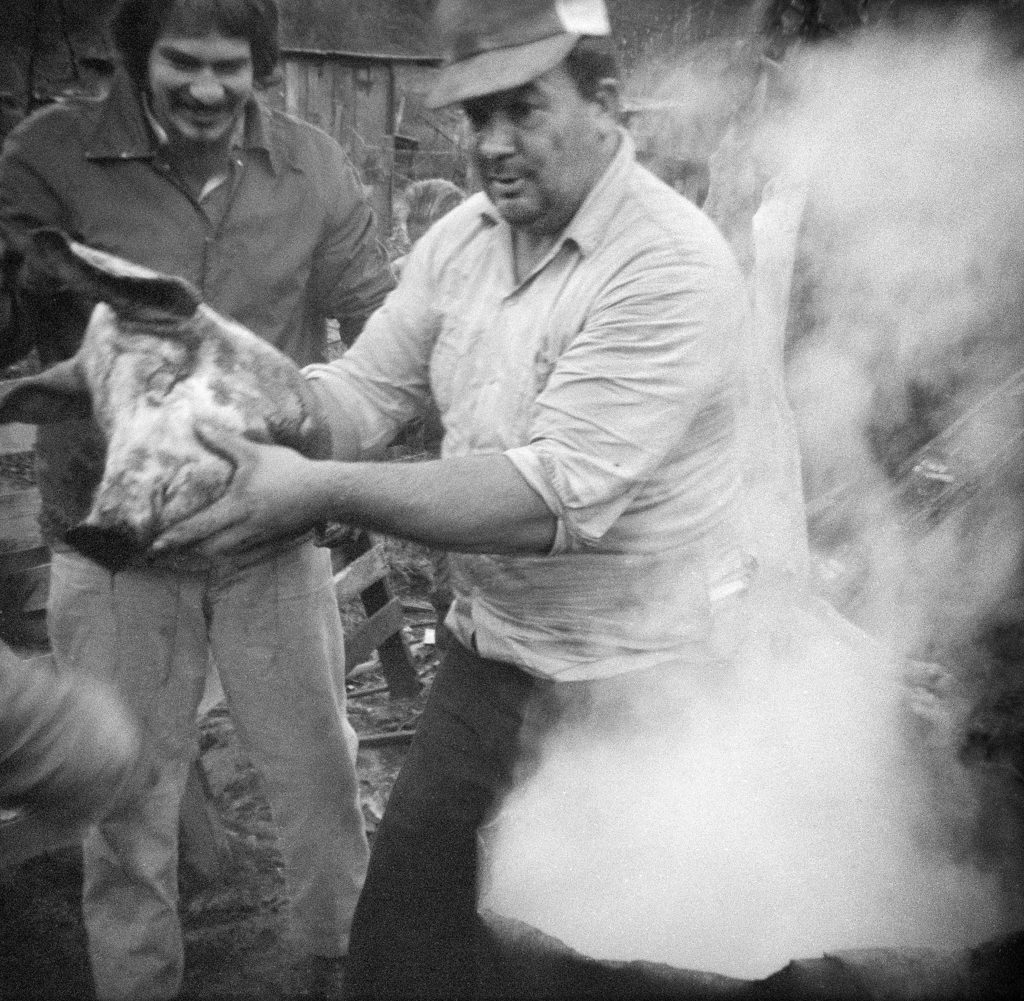

Children who might not have ever loaded a camera were likely to have learned how to clean a gun. They quickly apprehended the gap that existed between what they knew they had seen, and what the camera saw. They learned how to communicate to the camera, changing the angle or thinking more carefully about what a frame could contain, and what could be left out, just outside the visible. Because they themselves were still young enough to exist on the edges of the adult world, not quite yet key players, they could see clearly the rituals that surrounded them—smoke rising around hog killings, women hugging after church, men descending a dirt road as they departed the coal mines. One girl photographed the vases of flowers set on a linoleum floor around the casket of an infant—"my sister's baby's funeral." In the background, a woman is seen bottle-feeding a baby on her lap. As the critic Ben Lifson writes in an introductory essay to the book, "They seem to have walked up to their subjects and stopped when they saw them clearly and whole."

Mary Jo Cornett, Mamaw and my sister with a picture of the cousin that died, from 'Portraits and Dreams' by Wendy Ewald. Courtesy the artist and MACK.

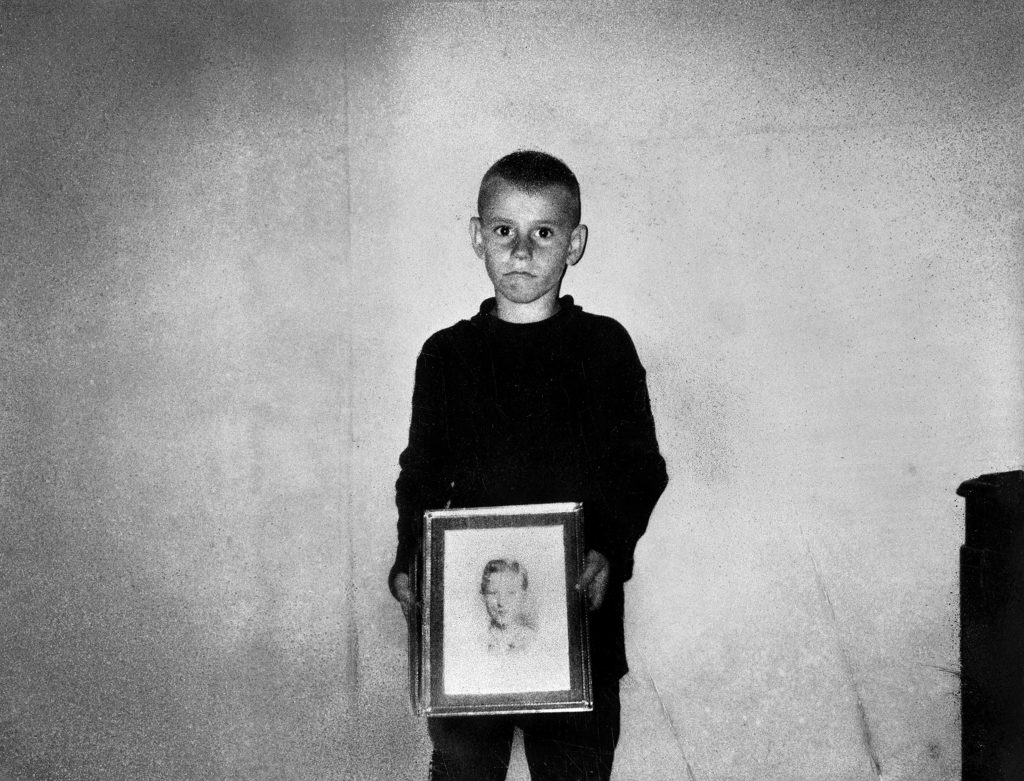

Ewald invited them to learn to see themselves through pictures by and of others, in the photo books she brought to the classroom. Prior to the classes, photography had entered the children's worlds primarily through newspapers, the photos adorning seed catalogues and record album covers, and the family pictures hanging on their walls. Ewald caught them at an age when they were unconsciously beginning to work out their own relationship to those family pictures—how they fit in, who they might become. Ewald's student Freddy Childers made a portrait of himself with his brother Homer, who has a disability; and also a portrait of himself holding a framed picture of his oldest brother Everett, who had committed suicide after returning home from Vietnam. Hovering around Ewald's students were the images of those who had passed on and the mysteries of the world of the grown-ups who carried those stories without sharing them. "He's not a guy you can walk up to and express yourself to, but he's not the hardest guy to live with either," Gary Crase said of his father. In Mamaw and my sister with a picture of the cousin that died, by Mary Jo Cornett, the sister in question bears an uncanny resemblance to the enlarged photo of the cousin, a vivid encounter with memory and history.

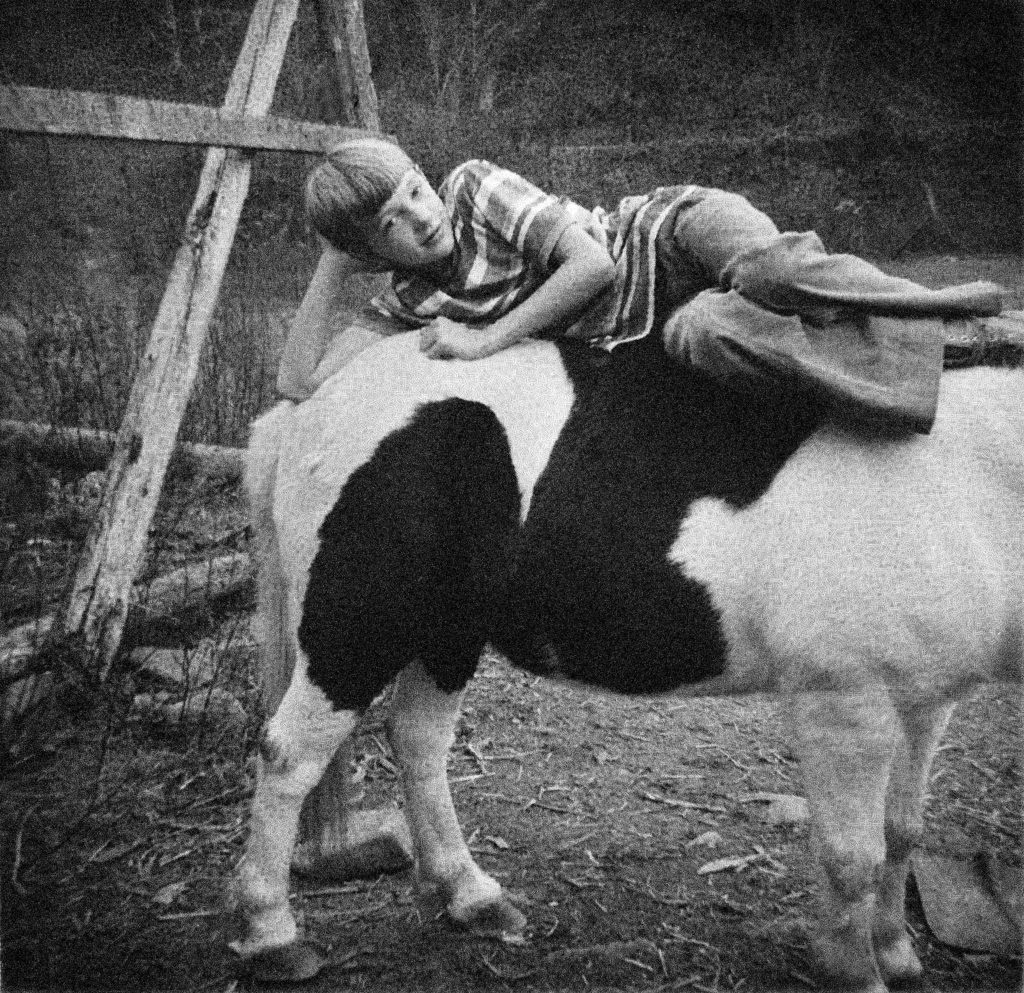

Russel Akemon, 'I am lying on the back on my old horse,' from 'Portraits and Dreams' by Wendy Ewald. Courtesy the artist and MACK

But Ewald also encouraged the children to see themselves as characters in their own self-portraits, often leaving the frame open to reveal their wider world. Russell Akemon lies casually on the back of "my old horse"; in another, portrays himself hunched against a tall haystack, nearly enveloped by it. Denise Dixon's blond wig helped transform her into Dolly Parton in one photo and a movie star in another, pouting and swooning in a nightgown with a snake around her neck, rumpled sheets and wood paneling visible behind her.

It is in the dreaming that they perhaps are most free. When Ewald guided them to illustrate their subconscious, the classes would first sit together in the darkroom and confess their scariest dreams. In Scott Huff's The planes were crashing on my head, model airplanes shower him as he cowers, covering his head, standing on a dirt road with a basketball hoop in the background. The crudeness of their props and costumes—goggles for astronauts, barn roofs and rock faces and crooks of trees to help show floating, falling, death—makes visible the contours of the imagination. Denise Dixon slips pantyhose over the heads of her baby twin brothers and photographs them in matching outfits on a patterned chair— Phillip and Jamie are creatures from outer space in their space ship, the photograph is titled. In grainy black-and-white, with the intentional blur of movement, these photographs have the mystic quality of the work of their Kentucky counterpart Ralph Eugene Meatyard. "Sometimes when I'm in bed, I get lost on dreams," writes Darlene Watts. The children's photos are enigmatic and narrative but they also have the most ephemeral quality of all: the ability to capture a time before the dreams are forgotten.

Allen Shepherd, 'I dreamt I killed my best friend, Ricky Dixon,' from 'Portraits and Dreams' by Wendy Ewald. Courtesy the artist and MACK.

Like kids anywhere, they drifted into other things. Denise Dixon got wrapped up in playing basketball and cheerleading. Others grew up fast, quit school, got jobs in the mines or at the local Pizza Hut; they got married, set their sights on college. Ewald went on to work with students around the world, and to start the project Literacy Through Photography, which is still housed at the Center for Documentary Studies at Duke University. In 2008, when Ewald began to reconnect with her Letcher County students (a reunion documented in additional material included in the book as well as in the film Portraits and Dreams currently streaming on PBS) she met her students in their forties, in the midst of the adult world they had once observed together. Many had returned to the mountains they'd photographed in their youth. They were engineers, teachers, parents, meat-processing workers, and miners. Some had fallen on tough times. One student, foraging for a living after getting laid off from work, was incarcerated briefly for a robbery. Several had resumed photography. Looking back, they, too, were struck by how the photos they had made then revealed their innermost thoughts, rather than the outward surfaces. "We were all poor, but we didn't know it," writes another student, Sue Dixon Brashear, who made photographic books during her own time as an elementary schoolteacher. "Didn't care one bit."

In 2018, looking back at the photographs he'd made—of a favorite chicken, of his father pulling a mule—Willie Whitaker, who'd become an operations manager for the Army Corps of Engineers, wrote to Ewald. He was working on a poem about his mother milking a cow, a memory from childhood, but the emotion, he confessed, had become "almost burdensome." For him the pictures were portals, not necessarily straight to the past but to a map of half-forgotten forked roads. "I always wonder once we lost our innocence would it be possible if the chicken was still alive, dad and that mule were still alive, would it be possible to recreate those photos?" he wrote. "Would we over-stage them? Would I be satisfied with Dad turning around the way he did?"

Here, in excerpts from four sections of Portraits and Dreams, are some of Ewald's Letcher County students' words and pictures.

Ruby Cornett, 'Daddy at our hog killing, Big Branch,' from 'Portraits and Dreams' by Wendy Ewald

Darlene Watts

When you're in love you do funny things like lay your books in the refrigerator. I think it sounds nice, but when it comes to marrying, I don't know. Marriage seems to suit everyone else. In some ways, I guess it would suit me too, but I worry that I won't be able to get along with my husband—not suit him. I'd like to have a perfect marriage, but that's hard to come by these days. I know one thing, when you get married, you can't lay your books in the refrigerator any more because your husband would get mad. He usually acts like he's the boss, and I don't like anyone to boss me around all the time. Sometimes I like to be free.

When I see all the pretty clothes, I think I'm lucky that I'm a girl. But sometimes I want to be a boy because I want to do some of the things boys do—like go hunting and fishing. I know some of the boys at school do the things girls do. My neighbors say that girls and boys are different because girls play with dolls and boys play with trucks.

Around here girls can get jobs in stores, or be a nurse, or run a restaurant, or babysit. I guess there should be more to choose from, so we wouldn't have to go off, say to Indiana, to get a job. There's lots of things I'd like to be, but I can't be them all.

Freddy Childers, 'Self-portrait with the picture of my biggest brother, Everett, who killed himself when he came back from Vietnam' in 'Portraits and Dreams' by Wendy Ewald. Courtesy the artist and MACK.

Delbert Shepherd

I put my chickens in a place where they can keep dry. I feed 'em corn and water 'em. I feed the little ones corn bread. I clean out a place where they can run around. Inside the hens is a hen bag that makes eggs everyday. The first time I saw a chicken killed, I felt like it was right sickening for somebody to do that to an animal. It didn't seem right that people wanted to have them around and then kill them, but I've learned it's for food. At first I couldn't eat the animals that I'd seen killed because I was scared. I've learned to try it and if I like it, it's all right, but I just think about somebody killing me. I think of what it must feel like. I think if I were a chicken, after they'd picked all my feathers off, they'd hold a paper bag over me and light it. I'd come out all in pieces—my legs, my neck, back, my breast, ribs, but it helps you to understand the way you're put together, the way God made you.

One of my friends fights chickens a lot. He fights big roosters. He buys these roosters that can't stay with another rooster. They think they're the boss, and when he puts two of them together, they try to kill one another to be the winner. Two boys each bet a dollar on one of the roosters. They're professional fighters, just like humans are boxers, but it's more like trying to kill one another—a killing match. They outlawed it because they thought it was being cruel to animals and I think it is.

You watch animals play and all of a sudden it comes naturally to you. You love them. You get attached to them, and you can't separate.

Birds communicate to birds. Dogs communicate to dogs. When a dog barks, it's trying to tell you something. You can't understand it, but a dog understands you. Animals are smart. If they weren't, a cat wouldn't know how to climb a tree. A duck wouldn't know how to swim.

Animals are smarter than people. They've lived out in the mountains so long, they know the way. They can go anywhere they want to. People can't. It took years and years for them to discover the wheel.

Animals can find food and protect people from enemies. They can sense danger that we can't. In the dark of the night they sense it, when it's right in front of them. Dad says it's more fun to hunt the animals than it is to kill them. He likes to watch their reactions, how they move. Where there's mountains, there's a lot more animals. They like higher places where hunters can't find them, and they know when you're in the mountains.

Greg Cornett, 'Gary Crase and his mom and dad in front of their house on Campbells Branch,' from 'Portraits and Dreams' by Wendy Ewald. Courtesy the artist and MACK.

Dewayne Cole

My father grew up in Daisy and my mother grew up on Turkey Creek. They went to school together. My mother's just about like any other mother. She does everything for me. She gets me up every morning and that's hard to do. She cooks for me. Cleans up my bedroom. Fixes me things to eat. I like her a lot. She has brown hair and black eyes. She's fat and short. I'm about as tall as she. I like the way she looks.

Dad works in the coal mines. Mom works in the kitchen and I work at books. My brother Bobby is just in the first grade. He's all the time botherin' you. And I've got one brother that's just in the last year of school and one that's already married. He works in the mines. His wife works in the kitchen and watches TV and listens to the radio, but she cleans up after him. He's a mess.

Our house sure wouldn't be any fun without my mother around, but I'm close to both Mom and Dad. My dad and I go hunting, work together. We build things. We're making a grease rack now, where he can work on his truck. We just about do everything together. I feel about my mom the same as I feel about my dad. When I have problems, he'll help me. My family works hard. They feel good about it, but they don't like to have to work all the time.

I don't feel too good about my dad working in the mines. It's dangerous. He's been hurt five or six times. A big hook on a cable cut him right through his forehead. He could stick four of his fingers down in under his eye. He stayed in the hospital for two weeks.

My mom doesn't like to talk about my dad getting hurt. My mother thinks sometimes that something's happened to my dad, but if he gets hurt, somebody always comes over and tells us, while they take him on to the hospital. Families here think about each other. They know everybody and every place. Anybody gets hurt and you know about it in a few minutes. News up here goes around fast.

The same old thing, day after day. You don't hardly notice things until they're gone. The mountains are big and I feel good in them. I can go anywhere. Nothing bothers me up there except now they're tearing the mountains up with bulldozers getting the coal out and making new places for houses. They're destroying them. They've killed almost everything that's up there. I'd like to plant trees and set animals out because soon there won't be anything to look at. It'll just be a plain old place. It makes me sad because I don't like to see anything destroyed, and the people that are destroying it are mostly from the big cities. One man came in here from California. He set the woods on fire because he wanted to burn a big place off where he could set his equipment. I don't like people from the cities. I don't like the way they talk and the way they dress. I just like seeing normal people around.

Denise Dixon, 'Self-portrait reaching for the Red Star sky,' from 'Portraits and Dreams' by Wendy Ewald (MACK, 2020). Courtesy the artist and MACK.

Denise Dixon

I like to take pictures from my dreams, from television, or just from my imagination. I like those kind of pictures because they're scary. If I didn't know how I took them, I'd be scared by them. My twin brothers, Phillip and Jamie, pose for me. Sometimes they're good at having their pictures taken but they get tired.

I made a long dream with Phillip and Jamie which comes from TV shows I've watched. I told Jamie to lay down and then I put all this makeup on him to make scars and scratches on his mouth down through his nose and on his hands. I put wood on top of him like a house fell on him and I told him to act like he was dead. I took some in the graveyard above my house. For one I told Jamie to grab a hold of the gravestone and start screaming. For the other I told him to kneel down. I told him to bow down like he was sad. I took the picture from the foot of the grave that had just been filled.

I always think about what I'm going to do before I take the picture. I have taken pictures of myself as Dolly Parton and Marilyn Monroe and then there was the girl with the snake around her neck. She was supposed to be a movie star, but really it was me. For some I was dancing in my bathing suit while the music was playing in the basement. I told my girlfriend, Michelle, how far away to stand and to take the pictures when I said. I like people in action, and I always look for a certain time to take a picture of it.

Denise Dixon, Phillip and Jamie are creatures from outer space in their space ship, from 'Portraits and Dreams' by Wendy Ewald. Courtesy the artist and MACK.

Rebecca Bengal writes fiction, essays, and long-form journalism and lives in New York City.

plunketthiselon1952.blogspot.com

Source: https://www.theparisreview.org/blog/2020/10/08/the-children-of-the-appalachians/